In a recent post, we introduced a fast finality mechanism. In this post, we take a deep dive into the mechanism and address these questions:

How it differs from preconfirmations

How it may complement other finality mechanisms, like ZK-proof (ZKP) or Fraud Proof (FP)

Improvements and optimizations

What Is the Problem We Want to Address?

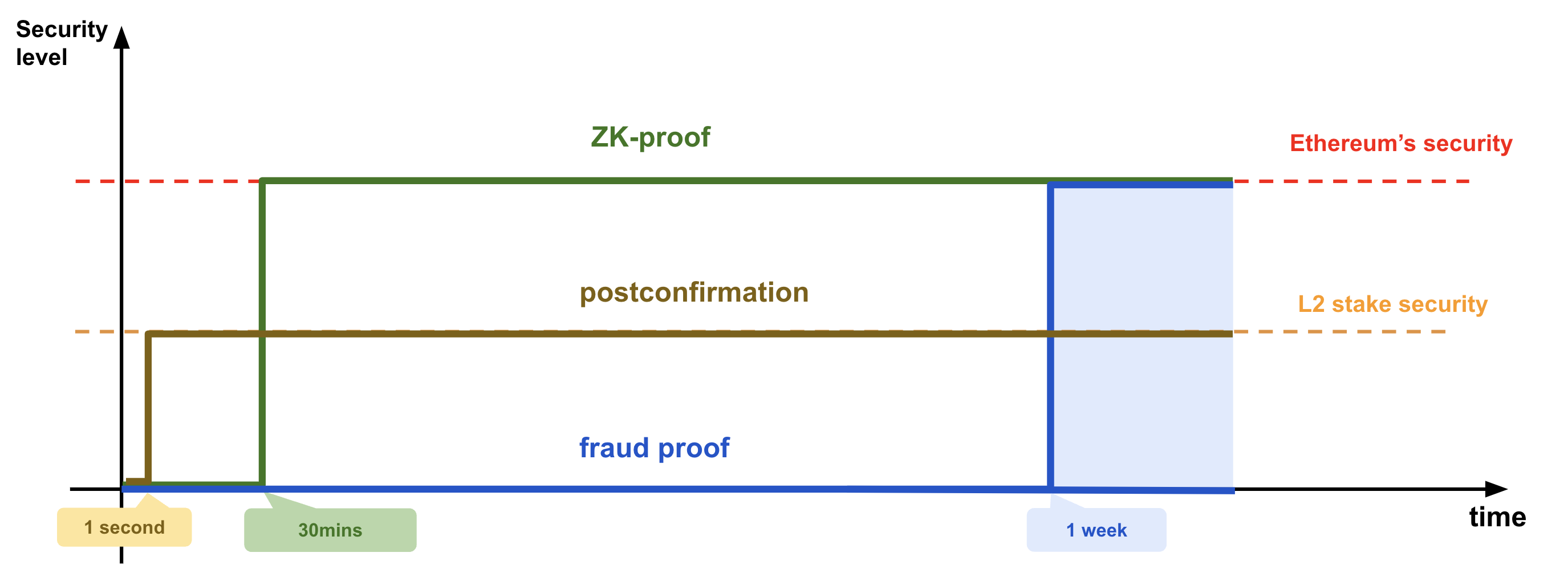

Layer 2s (L2) and rollups have to publish transaction data to a data availability (DA) layer or to Ethereum mainnet (Layer 1, L1). Validity (ZKP) and optimistic (FP) rollups can finalize (confirm) transactions within approximately 30 minutes (ZKP) resp. ~1 week (FP). Until a transaction is finalized, there is no assurance about its validity and result (success or failure). This can be a limiting factor for certain types of DeFi applications.

So the question is:

Can we design a mechanism that quickly provides some guarantees about the result of a transaction on an L2?

The answer is yes—with postconfirmation. This idea is summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Security levels and time to finality. The time to finality does not include L1 (Ethereum) average finalization time which is ~13 minutes. For ZK-proof, it is the time to generate the proof. And for fraud proof, it is in the order of 1 week, so 13 minutes does not make any difference.

ZK-proofs provide the maximum level of security and inherit Ethereum security (for a precise meaning of inherits, we refer the reader to this recent post); finality is ~30 minutes. Fraud proofs provide a level of security ranging from none (if the challenge period ends and no validator checks the result) to Ethereum's security; Finality is ~7 days for FP.

An intermediate level of security, L2 stake security, can be provided by the L2 via postconfirmation (we explain what they are in the sequel).

Postconfirmations are fast (~1 second) because they are delivered right after the execution of a block of transactions when a new block is created.

Overall, the user can now have some guarantees, quickly, about the result of their transactions, and can decide whether this is good enough to assume confirmation or to wait for L1 finality (with a ZKP or a FP) to get Ethereum's level of security.

Some centralized exchanges provide early confirmations of transactions based on the number of blocks that follow the block a transaction is in. However, there is no guarantee attached to this early confirmation unless finalization is provided by a longest-chain mechanism.

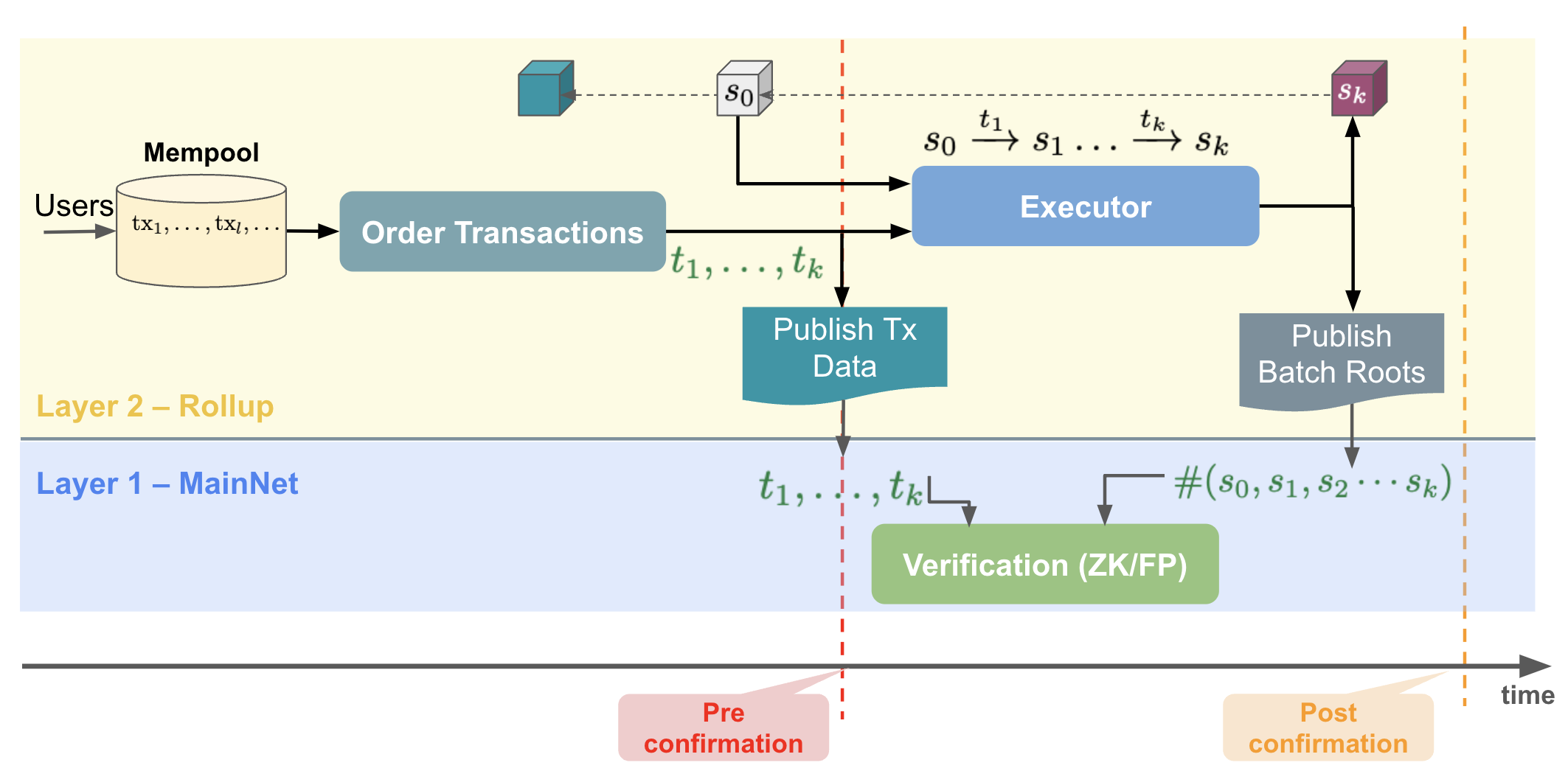

Preconfirmations vs. Postconfirmations

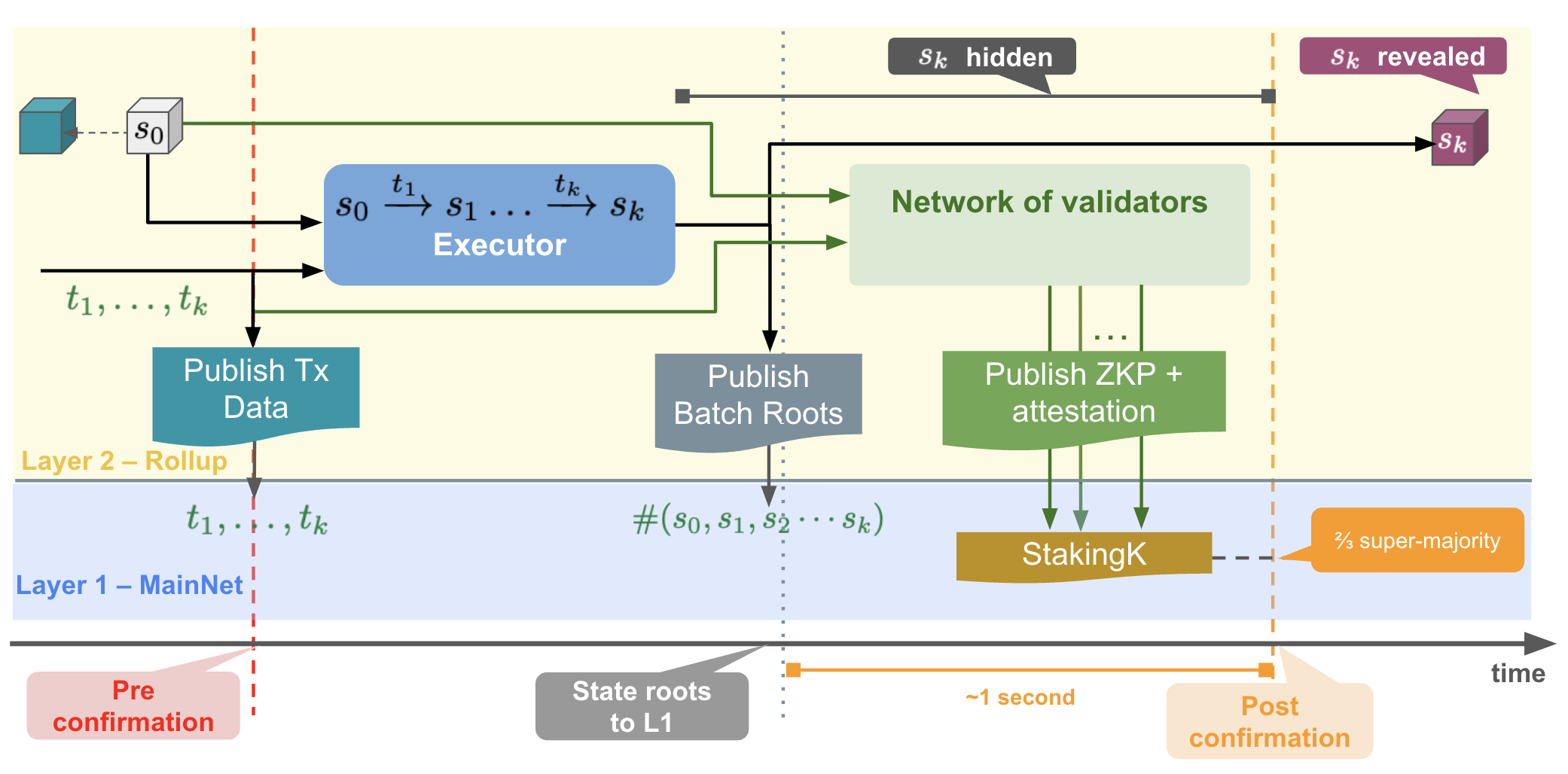

The mechanism we propose is to provide postconfirmations for L2 transactions. This is depicted in Fig. 2. This mechanism is different than preconfirmations as in based sequencing. It provides a guarantee that the new block is correct, not only that a transaction will be included (or executed). It is not a replacement for the complex execution tickets mechanism, as it does not provide a way to influence the creation of a block, but rather to report on the correct execution of the transactions in a block.

Figure 2: Confirmation stages of a transaction. Preconfirmation is a promise (by the sequencer) that a transaction will be included in the next block(s). In contrast, postconfirmation aims to offer some guarantees, backed by the L2 stake, that the new state (after the executor has processed a transaction) is correct.

How Does Postconfirmation Work?

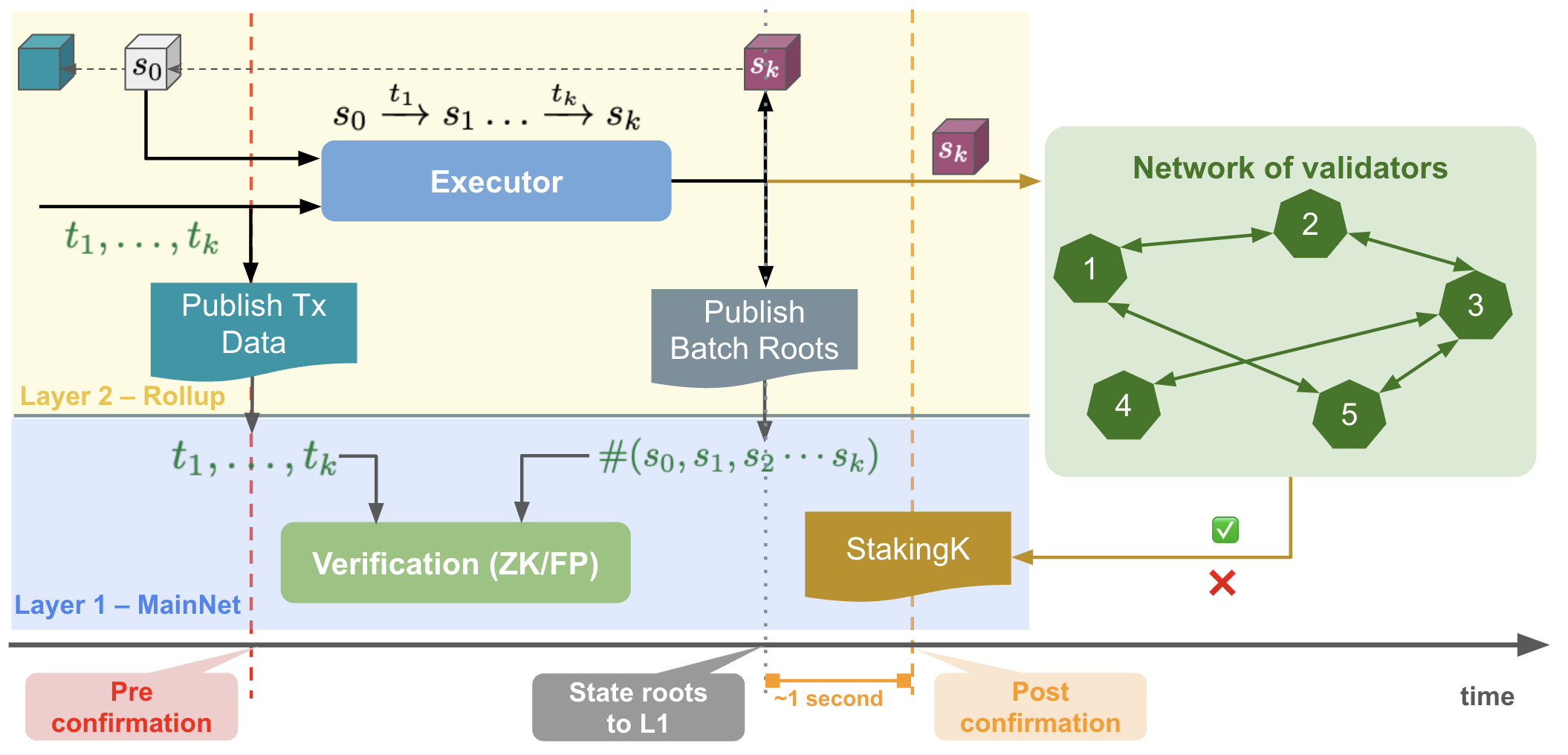

A network of validators (Fig. 3) is in charge of verifying new blocks. Each validator has to stake some assets in an L1 StakingK contract. We assume each validator stakes the same amount.

We assume that at most 1/3 of the validators can be dishonest (Byzantine). An honest validator attests (positively) for a block only if it is correct.

We refer the reader to this post for a precise definition of correctness.

Figure 3: A network of validators verify a new block. They submit their signed attestations confirming/rejecting a new block to a staking contract on L1.

A simple design (we refine it in the sequel) is that each validator sends their attestations ✅ or ❌ to the StakingK contract. Once the contract has received a 2/3 (super-majority) of positive ✅ attestations for a new block, the new block is postconfirmed.

What Confidence Can We Have in Postconfirmation?

Validators send their attestations to the StakingK and they cannot change or withdraw them and are committed to them. If later on (when verifying a block with a ZK proof or fraud proof) they are found to be incorrect (intentionally or non intentionally), they are slashed. As a result:

When they attest, they have an incentive to do so honestly, or otherwise they may lose their stakes.

They cannot undo their votes, and when 2/3 (super-majority) have committed their positive votes, we can have high confidence that a new block is correct. This holds even if the execution of the transaction (

StakingK) that checks the super-majority has not been finalized yet on L1.

If the total stake in the StakingK is large, it is hard for an attacker to control more than 1/3 of validators to prevent obtaining a super-majority, and even harder to control 2/3 to validate an incorrect block. The L2 stake security level (Fig. 1) can get close to Ethereum's security level if enough validators (and stakes) participate in the network.

The StakingK contract manages the stakes (staking, rewarding, and slashing) and is assumed to be correct (free of bugs). It offers a function to receive the signed attestations and to verify the signatures along with the 2/3 super-majority threshold. It is executed on L1 and its execution inherits Ethereum's security.

In this design, there is no requirement for validators to re-compute the new block to verify it is correct. They only have to ensure that when they attest positively, this new block is correct (so they could attest without performing any check). Moreover, the previous simple design may be quite expensive if each validator issues an L1 transaction to cast their attestations. We address these two limitations in the next sections.

Aggregating Attestations

To make the attestation process more efficient, we can require the validators to run an L1 light client. They have access to the state of StakingK and can determine themselves how many validators are active.

An active validator is a validator that has not been slashed of their stakes. We assume here that the slashing mechanism slashes the entire stake of a validator if they are slahed.

The validators can broadcast their votes for a new block to the entire validators' network. The validators can record and aggregate signed attestations. When one of the validators has determined that the 2/3 super-majority is reached, they can send the aggregated (signed) attestations to the StakingK contract. This reduces the number of L1 transactions needed to record the attestations.

We should also note that:

The validators record both positive ✅ and negative ❌ attestations and send both types of attestations to the

StakingK. Once a 2/3 super-majority is reached, theStakingKcontract can slash the validators that attested negatively, as they are dishonest (under the assumption that at most 1/3 of validators can be Byzantine).As validators rely on a recent state of

StakingKcontract (to compute what the 2/3 majority threshold is), we have to prevent validators from withdrawing their stakes too quickly. This is to ensure that a dishonest validator cannot wrongly/dishonestly attest and then withdraw their stakes before being slashed. We can lock the stakes for a pre-defined amount of time (a few epochs).It does not matter whether an honest or dishonest validator posts the aggregated signatures. Assuming signatures cannot be tampered with, a dishonest validator can only withhold some signatures or not posting anything to the L1, but cannot forge an invalid set of attestations.

Commitment Hiding

As mentioned, validators could attest without checking a new block. For instance, if a validator has collected more than 1/3 of positive attestations, they could blindly attest positively too (assuming at most 1/3 of validators can be Byzantine this is low risk).

To incentivize validators to do some actual verification, we can ask them to provide a proof that they have re-computed the new block (if no ZKP exists yet, this is the only way to check the correctness of a block).

Figure 4: The new block/state is not revealed until 2/3 of the validators have attested for it. Validators can submit (ZK) proofs along with their attestations.

In this set up (Fig. 4), we have to keep the new block/state hidden until a 2/3 majority has attested for it.

To do so, we can send the sequence of transactions 𝑡1,⋯,𝑡k, the source state 𝑠0 and a hash, #𝑠𝑘, of the new block/state 𝑠𝑘 without revealing the new state 𝑠𝑘 for now. Validators can broadcast a positive attestation together with a ZKP that they know a state 𝑠′ the hash of which is the same as #𝑠𝑘 (this is easier to compute than a ZKP of the entire execution of transactions). As a hash function cannot be reversed and is collision-free, if they know such a state 𝑠′ this implies that:

𝑠𝑘 is the same as 𝑠′

They must have re-computed (with high probability) the new state 𝑠′ (it is very unlikely they guessed it)

This provides even more confidence that a new block/state is correct, as it enforces its verification. At the same time, it enables us to weaken the trust assumptions in the sense that we may not need to assume that honest validators re-compute the new state, they have to prove it.

We can still allow validators to submit attestations without a proof, but they may get a smaller reward compared to those who do more (verifiable) work.